China’s space weather observatory is largest network of ground-based monitoring on Earth

China has achieved a world first in space weather monitoring, with the completion of the largest network of ground-based observatories on Earth, stretching across the country in two bands from north to south and east to west.

The Chinese Meridian Project, led by the National Space Science Centre (NSSC) in Beijing, took eight years and more than 1.5 billion yuan (US$212 million) to build and could eventually form the basis of an international monitoring programme.

NSSC director Wang Chi, the project’s chief commander, said the breakthrough would help researchers to better understand the “whole process” of space weather, which is known to disrupt satellite operations and knock out power grids on Earth.

“For the first time, the Chinese Meridian Project will achieve end-to-end monitoring – from the sun to solar-terrestrial space to Earth’s atmosphere,” he told state broadcaster CCTV.

“It will not only safeguard China’s major space infrastructure for national strategic needs, but also push Chinese scientists to the forefront of space weather research,” he said.

The project, funded by China’s National Development and Reform Commission, was developed out of the growing need to better understand and predict solar activity and its potentially devastating effects on a range of technologies.

The network’s nearly 300 instruments – which include some of the world’s most powerful – are built between longitudes 100-120E and latitudes 30-40N and eventually could form part of a global version for all-time, all-weather space monitoring.

The International Meridian Circle Programme (IMCP) was envisioned more than a decade ago by researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and aims to eventually encompass 5,000 instruments across dozens of countries.

In the first phase of the Chinese Meridian Project’s construction, 87 instruments were installed, from the northernmost city of Mohe to the island province of Hainan at China’s southern tip, and from Shanghai on the east coast to Lhasa in the far west.

The joint effort – involving 12 institutes and universities working together between 2008 and 2012 – combined radar, ionosondes, magnetometers, sounding rockets and other facilities to enable an interdisciplinary survey of near-Earth space weather.

Researchers were able to study the different layers of the near-Earth space environment, from the middle and upper atmosphere, through the ionosphere and magnetosphere, to interplanetary space.

From 2019 to 2023, about 200 instruments were added in the network’s second construction phase. It now boasts 44 categories of instruments, some of which are “hard-core” and the most powerful of their kind in the world, Wang told CCTV.

Space physicist Shun-Rong Zhang, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Haystack observatory in the US, said the scale, diversity and geological distribution of the equipment in the Chinese network is impressive.

Most of the observation instruments have existed in the US and Europe for some time, but they are usually operated by separate research teams at different institutions and universities, he said.

“By integrating all the equipment into one network, China will be able to manage them systematically and coordinate observations more efficiently.”

The mass effect, as well as the unique individual facilities in the network, will help China make major contributions to space weather monitoring and space physics research in years to come, Zhang said.

MIT’s Haystack Observatory was one of the NSCC’s first partners in the IMCP, helping to conceptualise the global network, set the programme’s scientific agendas, and train young talent.

In 2010, the NSSC signed agreements with research institutions in the US, Russia, Canada, Brazil, Japan and Australia to work together on a network that would encircle the globe along the 120E/60W meridian.

Today, IMCP participants include the National Institute for Space Research in Brazil, the Institute of Solar-Terrestrial Physics under the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the French National Centre for Scientific Research, as well as MIT.

The proposal for an IMCP was triggered by the growing need for more accurate predictions of solar activity – including the geomagnetic storms caused by highly-charged particles from the sun triggering disturbances in the Earth’s magnetosphere.

The entire Canadian province of Quebec lost power for nine hours in March 1989 because of a geomagnetic storm.

And in February 2022, 38 satellites plunged back into the atmosphere in a SpaceX Starlink mission because the pre-launch space weather forecast failed to mention that a geomagnetic storm was in progress.

The Daocheng Solar Radio Telescope (DART) at the western end of the Chinese network in Sichuan province, has been operational since June and is aimed at detecting a type of solar activity called coronal mass ejection, a main cause of geomagnetic storms.

DART is the world’s largest synthesis aperture radio telescope, with more than 300 dishes, six metres (19ft 8in) in diameter, forming an enormous circle on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau.

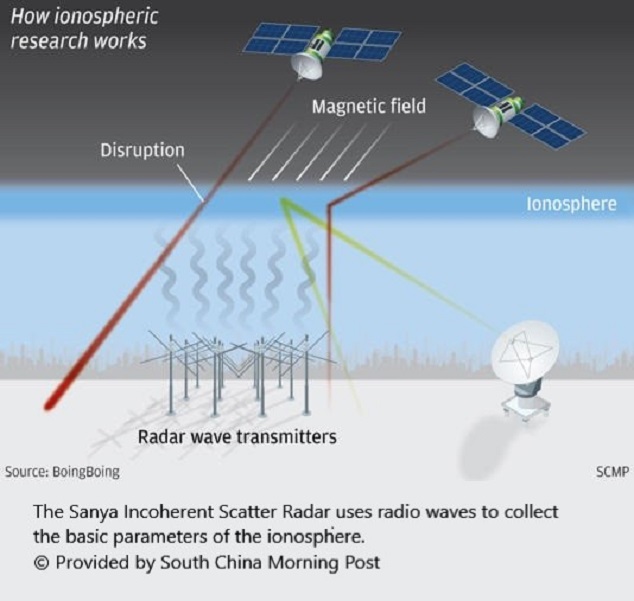

Meanwhile on Hainan Island, one of the world’s most advanced ground-based detectors of ionosphere dynamics – the Sanya Incoherent Scatter Radar – can beam radio waves up to 1,000km (621 miles) above the Earth.

The installation is based on more than 8,000 antenna units and a phenomenon known as Thomson scattering, which it uses to collect the basic parameters of the ionosphere, where many communications, broadcasting and navigation satellites are in orbit.

Emeritus professor Michel Blanc from the Research Institute in Astrophysics and Planetology in France, said the equipment developed during the Chinese Meridian Project’s second phase would be “a game-changer in 2024”.

“The Sanya incoherent scatter radar, lidars, radioheliographs, interplanetary scintillators, etc – this is really impressive,” said Blanc, who is also involved in the international project.

“For the IMCP, everything has to be imagined on how to move from the scale of China to a fully world-scale project,” he said.

The IMCP is a candidate for funding from China’s Ministry of Science and Technology, as a China-led international big-science project.

“If IMCP gets selected [for funding], it will really start using the unique impulse the Chinese Meridian Project has given to space weather research in China,” Blanc said.

Source: South China Morning Post, 2 Jan 2024. https://www.msn.com/en-xl/news/other/china-storms-ahead-in-space-weather-research-with-largest-observatory-on-earth/ar-AA1mlzvk