China’s grassland ecological compensation policy improves grassland quality and increases herders’ income

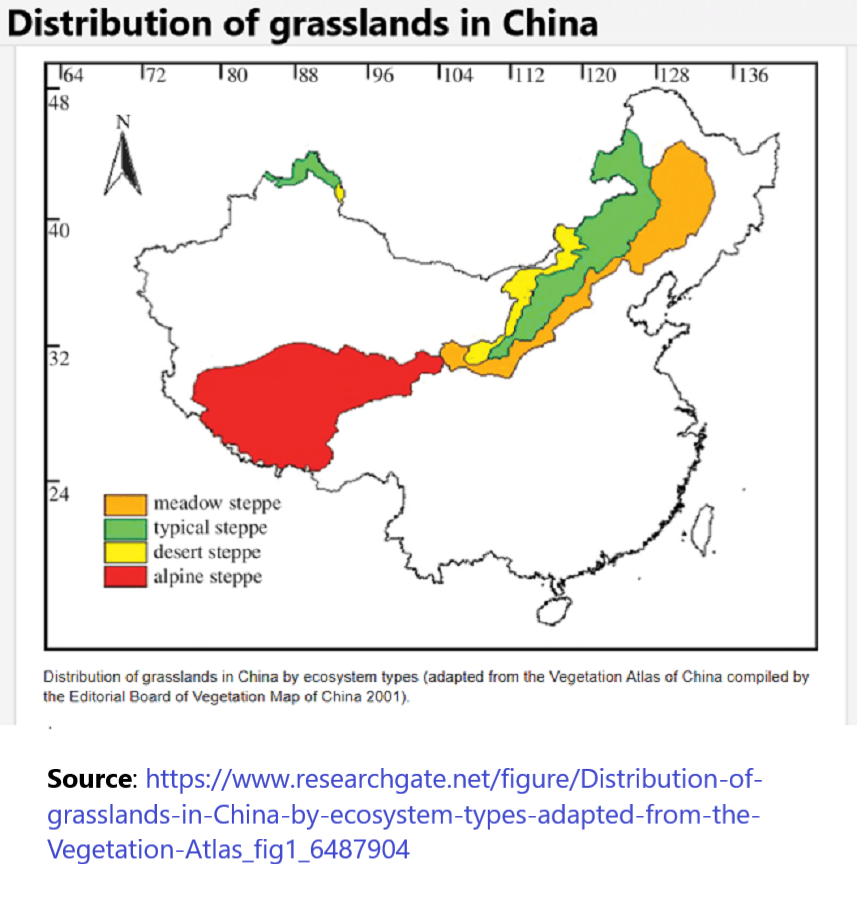

The grasslands of China are a vital ecological and social-economic resource, covering 40% of the national area and serving as an ecological barrier in the north and northwest border of China.

The grasslands have multiple functions, including adjusting climate, preserving water resources, fixing carbon and releasing oxygen, and mitigating wind and sand dusts – for the big northern cities of Beijing, Tianjin and Shijiazhuang, these grasslands are a last line of defence against devastating sandstorms that batter these cities every year. They are also the essential resources for agricultural productions and home to millions of herders of diverse ethnic groups. However, the deterioration of grassland in China is widespread, associated with overgrazing and overexploitation, as well as climate change.

The problem is not a particularly Chinese one, with nearly half of all grasslands worldwide experiencing degradation. Grasslands account for 40% of the world’s land area (excluding Antarctica and Greenland) and support around 1 billion people’s livelihood. Yet despite the importance of grasslands, few countries have created ecological programs that protect their grasslands and the pastoralists whose livelihoods rely on them.

With the dual goals to restore grassland ecosystems and raise herder income, China’s Grassland Ecological Compensation Policy (GECP) is a rare example of a pastoralist-focused payment-for-ecosystem-services (PES) scheme, and is the world’s largest PES grassland conservation program in terms of area, the number of participants, and total monetary transfers.

Starting from 2011 China began implementing grassland ecological protection subsidies and incentive policies. As of 2021 these had been rolled out in 13 provinces and regions, including Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet, and Qinghai, to 657 counties with a cumulative investment of more than $21 billion USD (150 billion yuan).

China’s Grassland Ecological Compensation Policy (GECP) is a significant effort to restore and sustain the grassland ecosystem and lift the income of herders. It recognizes the value of grasslands in ecological and social-economic terms. The program pays herders for reducing their grazing intensity or cessation of grazing. It operates with two policy zones: the grass-livestock balance zone and the grazing ban zone. Each policy zone has its own payment standard, with payments currently at $16/hectare and $5.5/hectare for grazing ban zones and grass-livestock balance zones.

In China nearly 18 million herdsmen in pastoral or semi-pastoral areas live on grasslands, with grazing livestock as their most important source of income. To date, more than 12 million farmers and herdsmen have benefited – in the provinces and regions that implemented the subsidy, each receives an annual subsidy of $105 (700 yuan) per capita, and the average household income has increased by nearly $200 (1,500 yuan). In some impoverished counties in provinces such as Qinghai, the compensation policy income accounted for 65% of household income.

Evaluations of the GECP show that it has been able to improve grassland quality by reducing livestock production. It was also clear that GECP significantly increased herder income. One consequencer of this was that “labor was (at least partially) released from the pastoral sector, allowing herders to take on non-pastoral jobs. … it is through the non-pastoral jobs that the pressure on the grassland was reduced, as fewer households were relying on the grassland to make a living.”

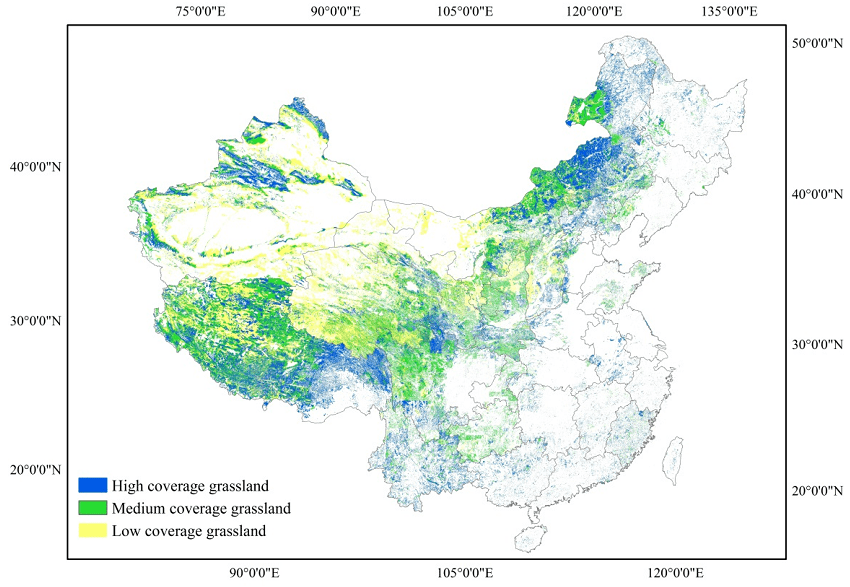

According to monitoring results, the national grassland comprehensive vegetation coverage increased from 51% in 2011 to 56.1% in 2020, and the output of fresh grass reached 1.1 billion tons. The number of grass species in the grassland prohibition area of Inner Mongolia increased from 8 to 12 per square meter, and the grass-livestock balance area increased from 12 to 46.

Environmental vs. development ?

As one of the largest of China’s grasslands, Inner Mongolia and the “dual-purpose” it presents for policy makers represents a significant conundrum for both regional and national governments as they look at how best to manage these vast areas of green, with major pressures for both better environmental protection and greater economic development.

On the one hand, Inner Mongolia’s importance as an ecological barrier to desertification and to reduce the impact of sand storms to China’s surrounding big cities is undisputed. Greater farming or building on these lands would further compound the severity of these yearly sandstorms, according to scientists, who are keen to see the grasslands preserved in the entirety.

Yet on the other hand, Inner Mongolia is an area in desperate need of investment and development. The region’s GDP ranked 22 out of 31 mainland provinces in 2020, as well as having the second slowest growth rate of any Chinese province last year, according to government statistics.

In recent years the balance appears to have firmly tipped in favour of environmental protection. These environmental policies are seen to be having an increasingly positive effect in limiting the yearly sand transported across China. And, rather than blocking economic opportunities for locals in the area, better protection of these grasslands is actually increasing the incomes of local people.

According to Beijing Review, “having only recently rid the area of absolute poverty, the country is now moving towards a new phase of development – known as rural revitalization – and to do that requires significant investment in all parts of the region, including the grasslands.”

Sources:

- Nature Communications 12, 4683 2021. Hou, L., Xia, F., Chen, Q. “Grassland ecological compensation policy in China improves grassland quality and increases herders’ income”. . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24942-8

- Sustainability 2023, 15(13), 10001; Jiayu Dong, Zimeng Ren, Xinling Zhang and Xiaoling Liu. ‘”Pastoral Differentiations’ Effects on Willingness to Accept Valuation for Grassland Eco-Subsidy”. https://doi.org/10.3390

- Beijing Review, 2021-08-13 ‘Protection or profit? The battle for China’s grasslands’, https://www.kitaichina.com/Opinion/Voice/202108/t20210813_800255540.html

- Charles Darwin University, Faculty of Science and Technology, ‘Ecosystem Services concept EV205’ http://learnline.cdu.edu.au/units/env205/module1/eco.html

- China News Service, 12/3/2021, ‘China’s grassland ecological compensation policy has been implemented for 10 years, 3.82 billion acres of grassland have been recuperated’, https://www.tellerreport.com/business/2021-12-03-china-s-grassland-ecological-compensation-policy-has-been-implemented-for-10-years–3-82-billion-acres-of-grassland-have-been-recuperated.rkMOqstPYF.html