Seven decades after Castle Bravo, the most devastating US nuclear test in the Pacific, the US still refuses to give the Marshall Islanders fair compensation

On March 1, 1954, a blinding flash of light in the west made it seem as though the sun was rising from the wrong side of the ocean. The sky and the sea turned red as a mushroom cloud swelled rapidly to a height of nearly 25 miles. Ash, water, and pulverized coral rained down. The people of Rongelap Atoll began to suffer from severe burns, nausea, and vomiting – symptoms of acute radiation sickness.

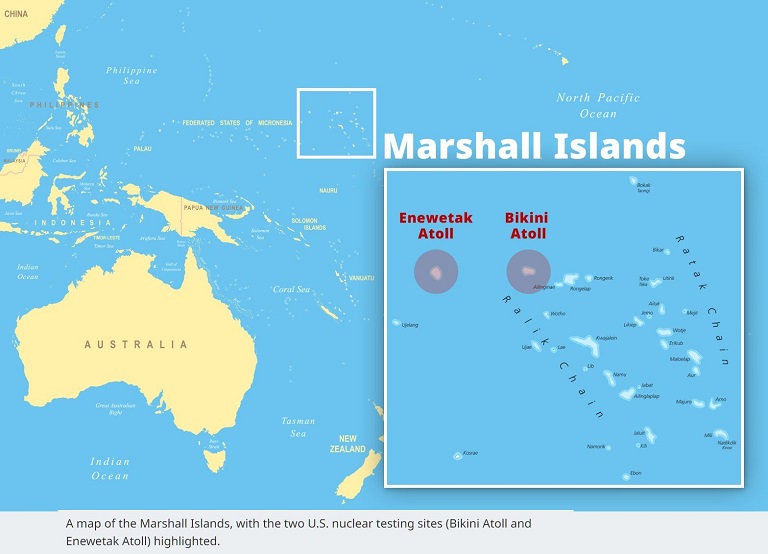

This was the experience of the closest witnesses to Castle Bravo, a thermonuclear weapon detonated by the United States on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands 70 years ago. The sunrise they saw was the explosion of a 15-megaton bomb, the most powerful weapon ever used by the U.S. military, 1,000 times larger than the blast that leveled Hiroshima.

On March 1, 2024, as every year, Marshallese flags will be flown at half-staff in remembrance of victims and survivors of nuclear testing.

Bravo was one of 67 nuclear tests conducted by the United States in the Marshall Islands from 1946 to 1958; the U.S. military controlled the islands from the end of World War II until 1947, when they became part of a U.S.-administered trust territory. The tests yielded as much radiation as 1.6 Hiroshima bombings every day for 12 years, and the Marshall Islands continues to suffer from their legacy – including high cancer rates, environmental degradation, and cultural dislocation – which the U.S. government has done little to redress. Nor has Washington rectified a series of its own cover-ups and human rights abuses, which still poison its relationship with the Marshall Islands.

The United States subjected the Marshallese people to scientific study without their consent; destroyed their health and their environment; lied to them about their radiation exposure; evacuated them too late, or not at all; knowingly resettled them on contaminated land; and displaced them – often indefinitely – from their homes.

Marshallese leaders have long sought fair compensation and an apology from the United States, and their position is supported by the United Nations and over 100 arms-control and environmental groups. Now, as Washington seeks to reengage in the Pacific during a new Cold War, nuclear justice has become even more essential for positive relations with the Marshall Islands and improving U.S. standing in the region.

Lies, Broken Promises, and Human Experimentation

Nuclear testing began in 1946. U.S. Navy Commodore Ben Wyatt, military governor of the Marshall Islands, asked the Bikinian people to leave their home “temporarily” so that nuclear tests could be conducted there for “the good of mankind and to end all wars.” The islanders’ agreement was irrelevant: the U.S. government had already designated Bikini as a test site. Many Bikinians later said they felt they had no choice but to leave.

The U.S. military relocated them to resource-scarce Rongerik Atoll, and by 1948 they were starving. They were moved again to Kili, which was little better. Today they cannot return home as they were promised; Bikini remains uninhabitable.

Among all the devastating effects of nuclear testing on the Marshall Islands, Bravo stands out as an exceptional tragedy. In 1982, the U.S. Defense Nuclear Agency called it “the worst single incident of fallout exposures in all the U.S. atmospheric testing program.” Radiation spread over 7,000 square miles, about the area of New Jersey, and traces were detected around the world.

But it wasn’t Bravo’s magnitude alone that made it dangerous; it was the actions and inactions of the U.S. government. The United States hadn’t evacuated atolls near the test site – the closest, Rongelap and Ailinginae, were less than 100 miles away. Children played in the radioactive ashfall, not knowing what it was. No one but U.S. personnel had been warned about the test. Radioactive particles reached other inhabited atolls including Ailuk, Likiep, and Utirik.

The U.S. military waited until March 3 to evacuate Rongelap and Ailinginae, and until the day after to evacuate Utirik. By then, many Marshallese were sick from radiation. The United States later blamed shifting winds for fallout east of Bikini, but the U.S. military knew the winds changed hours before the test and still failed to make swift evacuations. Hundreds of people living on Ailuk and Likiep were never evacuated, even though U.S. ships were close enough to help.

Then the U.S. government lied about the danger. Radioactive material had fallen on a nearby Japanese fishing vessel, and when the crew returned home with acute radiation sickness, the world learned of Bravo and the “ashes of death” it had unleashed. The word “fallout” was born, and with it an international campaign against nuclear testing. In response, the erstwhile U.S. Atomic Energy Commission claimed that only three islands besides Bikini were contaminated. But the U.S. government knew that more than a dozen atolls had received significant radiation from Bravo, according to documents declassified in 1994.

The immediate and long-term health effects were catastrophic. U.S. officials claimed that the people of Rongelap showed no signs of exposure, despite visible burns, lesions, and hair loss. Rongelapese women suffered miscarriages and stillbirths, and “jellyfish babies” were born without bones. One third of Rongelapese developed thyroid abnormalities, and 90 percent of Rongelapese children developed thyroid tumors. A U.S. medical program was established for Rongelap and Utirik, but thousands of Marshallese from other islands affected by Bravo and later tests remain ineligible because the United States hasn’t acknowledged the range or severity of the fallout.

Six days after Bravo, the U.S. government began its most dehumanizing policy, Project 4.1, in which American scientists studied the effects of radiation on the Marshallese people without their knowledge or consent, according to information declassified in 1994. Marshallese statesman Tony deBrum told the U.S. Congress in 1996 that American doctors had extracted people’s teeth, both healthy and unhealthy, for scientific research. Male U.S. scientists forced Marshallese women to undress in front of them. The program lasted decades.

During that time, the U.S. government purposefully resettled islanders on contaminated atolls. In 1956, Atomic Energy Commission director of health and safety Merril Eisenbud called Rongelap “by far the most contaminated place in the world.” He therefore recommended sending the Rongelapese people back in order to study their uptake of radiation, which he justified by describing them as uncivilized and comparing them to “mice.” In 1957, the U.S. government proceeded to resettle Rongelap, promising that it was safe, in what one U.S. official later called a cover-up. Bikini was likewise resettled and then re-evacuated in the 1970s after Bikinians had ingested high levels of radiation.

U.S. Policy Must Change

Like the sun rising in the west, U.S. policy toward the Marshall Islands is backwards.

In 1947, the U.N. gave the United States a legal responsibility to protect the health, lands, and resources of the trust territory’s inhabitants, but the U.S. government failed in that duty. In 2004, the U.S. National Cancer Institute found cancer to be the Marshall Islands’ second-leading cause of death; meanwhile, the country has no oncology center. A 2012 U.N. report determined that nuclear testing caused “immediate and continuing effects on the human rights of the Marshallese,” including deaths, long-term health complications, displacement, and “near-irreversible environmental contamination, leading to the loss of livelihoods and lands.”

The Marshall Islands has never been fairly compensated. In 1986, the country received $150 million in nuclear compensation from the United States under the Compact of Free Association (COFA). Additional funds for relocated communities brought total compensation to $600 million. The United States calls the 1986 agreement a “full and final settlement,” but the Marshall Islands doesn’t accept it as sufficient. During negotiations, Marshallese leaders lacked crucial information that was later declassified: the range of fallout, Project 4.1, and more. Nor could they negotiate equally with the United States because they didn’t have independence until signing the COFA. Like the people of Bikini asked to relocate, they had no choice.

The settlement was fundamentally inadequate. In 1991, the independent Nuclear Claims Tribunal, established by the COFA to adjudicate compensation claims, sought $2.3 billion from the United States – over $3 billion in today’s dollars. In addition, the COFA includes a provision allowing the Marshall Islands to request additional compensation for loss or damage from nuclear testing if such loss or damage was discovered after 1986. Overwhelming evidence fits this provision, but Marshallese petitions for compensation were rejected or ignored by the U.S. Congress in the 2000s, the U.S. Supreme Court in 2010, and U.S. negotiators during COFA funding negotiations in 2022-2023.

The United States’ domestic policies also demonstrate that $600 million is inadequate. Over $2.5 billion has been given to American nuclear-affected communities – and it’s not enough, but it is far more than the Marshallese have received. Last year the U.S. government even expanded nuclear compensation to Guam, over 1,000 miles from Bikini, while continuing to dismiss Marshallese negotiators.

The disparity is all the more glaring because the Marshallese were exposed to exponentially more powerful weapons than the U.S. population. The United States conducted over 1,000 nuclear tests during the Cold War, and less than 7 percent were in the Marshall Islands, but those produced 59 percent of the megatonnage of all U.S. nuclear tests.

The Marshall Islands has a special relationship with the United States under the COFA. It receives U.S. programs and services, gives the U.S. military exclusive operating rights in its islands, airspace, and territorial waters, and its citizens enlist in the U.S. military at a higher per capita rate than any U.S. state. Marshallese deserve more from the U.S. government.

The White House has never apologized to the Marshall Islands for nuclear testing or connected policies. In 1994, in response to newly declassified materials, a U.S. government committee concluded that exposure of the Marshallese people to radiation was not motivated by research purposes. The U.S. government has touted the report as if it absolves wrongdoing. The fact remains that Project 4.1 was unethical, and that much radiation exposure could have been avoided if the United States had conducted full and timely evacuations, provided true information, and not resettled the Marshallese on contaminated atolls.

Some experts conclude that the United States won’t apologize to the Marshall Islands because it would be expected to apologize to nuclear-affected U.S. citizens too. But there is precedent for the U.S. government apologizing for some of its worst domestic policies, including slavery, the Jim Crow laws, the internment of Japanese Americans, and the Tuskegee experiments. The harm of nuclear testing in the United States and its former territory also deserve acknowledgement.

Others says the U.S. government won’t apologize because nuclear testing strengthened national security, but this just underscores how much the United States owes the Marshall Islands. Nuclear testing wasn’t for the good of mankind, but for U.S. strategic interests: building its nuclear arsenal, maintaining its Cold War security doctrine, and propelling it to superpower status. In other words, nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands paid for American security. Bravo itself illustrates this: the test allowed the United States to catch up with the Soviet Union, which in 1953 had built a hydrogen bomb deliverable by airplane.

After Bravo, the Marshallese people petitioned the United Nations to halt nuclear testing because of the overwhelming harm to their health and islands, but their requests were denied. Marshallese leaders continued fighting back, from Tony deBrum, who witnessed Bravo as a child and campaigned against nuclear proliferation as foreign minister, to Darlene Keju, a public health worker, educator, and advocate for survivors of nuclear testing. Both have passed away, but they are followed by a new generation of Marshallese leaders fighting for nuclear justice.

As Bravo’s 70th anniversary dawns, it’s time for Washington to finally make things right. The Marshall Islands National Nuclear Commission stated in 2019: “We know we will obtain nuclear justice when the health of the Marshallese people and our islands is restored, when displaced communities are returned to or compensated for their homelands, when the full range of damages and injuries stemming from the program is acknowledged and compensated by the U.S. government.” Nuclear justice is long overdue.

Source: The Diplomat, March 01, 2024. https://thediplomat.com/2024/03/ashes-of-death-the-marshall-islands-is-still-seeking-justice-for-us-nuclear-tests/