Wild China – Toward a greater appreciation of wilderness

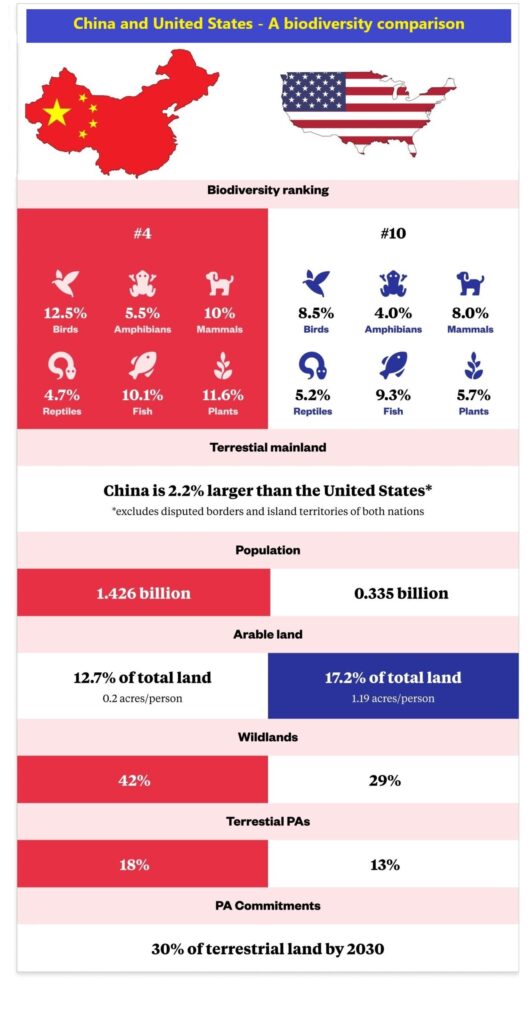

China is the world’s fourth most biodiverse nation. It has more large carnivore species than any country on earth, equivalent to that of the entire African continent. More people, too, but squeezed into only about a third of the land.

China’s mega-biodiversity is due to what Tibetan-Sichuanese writer Alai calls “the earth’s staircase,” the stunning transition from China’s eastern plains, basins, and low mountains to the Himalayan uplift, the roof of the world. Sipping tea near sea level in Chengdu on a clear day, if you gaze above the clouds 75 miles beyond the glittering skyscrapers, you can glimpse Yaomeifeng towering 20,000 feet above the entirety of eastern China. Go a little farther, and there’s Minya Konka (known in Chinese as Mt. Gonga) near 25,000 feet.

Where these peaks scrape the clouds and the earth buckles into ranks of mountains cut by roaring rivers is a biodiversity hotspot known as China’s Southwest Mountain zoogeographical subregion. It’s one of 19 total zoogeographical regions that define the nation’s landscape and biodiversity across tropical rain forest, cold desert, grassland, permafrost, and more. Within these regions hide patches of wilderness, areas of protected and unprotected water and land devoid of roads and human settlement. And while many living in China’s megacities fall into the trap of believing wilderness in China to be a misnomer, in 2019 a team based out of Tsinghua University published an incredible, eyebrow-raising statistic: 42% of China is wilderness.

“When we started our research, everyone was arguing whether China had wilderness or even if so how much it had. So this debate needed a scientific answer,” says Cao Yue, an assistant professor at Tsinghua University’s Department of Landscape Architecture and the lead author of the paper that contained the original study and statistic.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines a Wilderness Area as “usually large unmodified or slightly modified areas, retaining their natural character and influence, without permanent or significant human habitation, protected and managed to preserve their natural condition.”

In many Western nations, the lines between believed civilization and imaginary wild have long been divided along park boundaries, puny native reservations, and private land. Wilderness etymologically means “the place of wild beasts,” leaving no space for humans in the minds of early explorers, conservationists, and land management officials.

This legacy fits IUCN’s definition best — a clear separation between anthropogenic nature and nature left alone. But, in China, much of the county’s identified wilderness overlaps with traditional use areas. Patches of undeveloped land that would identify via satellite as wildland are frequented by villagers for local resources or used by nomadic peoples across seasons.

Even areas often called pristine, like eastern Tibet, were heavily deforested by indigenous peoples for thousands of years to create south-slope-facing winter pastures for grazing yaks. Native Americans in Yosemite Valley similarly altered the land for agriculture, clearing conifers to create glades of black oaks for acorn harvesting. Vestiges of these oak-strewn meadows and cleared south slopes still exist today.

So wilderness’s definition is globally contentious, dependent on the span of time observed and perspective of the speaker. Given China’s mix of cultures and breadth of history, defining a Chinese version of wilderness that follows the rules is exceptionally difficult.

“The definition needs to be flexibly understood. I think what is most important is understanding a landscape’s distinctive features,” Cao argues. He points to the holy mountains and lakes in Tibetan culture that qualify as sacred natural sites under the IUCN, which now recognizes such sites as “the oldest form of protected areas.” These sacred sites, Cao says, though sometimes frequented by humans, also contain wilderness features.

Cao and his team are now translating the IUCN’s wilderness management guidelines into Chinese, which includes the value of traditional indigenous lifestyles and multiculturality into the value of wilderness. Their wilderness data of China is also being used by wildlife conservation researchers and national park planning officials to plan wildlife corridors for endangered species like the North Chinese leopard and new protected areas across the country.

The most popular modern Chinese word for wilderness is huāngyě 荒野. It conveys a certain sense of barren desolation combined with primitive, even untamable, wild. The more appreciative phrase, yuánshǐ zìrán 原始自然, refers to original, untouched nature, and is often used in a more sentimental or scientific context. But the term shānshuǐ 山水, used throughout China’s ancient poetry and art, predates them all. Scholars who use it to study the roots of Chinese wilderness philosophy often come to a common conclusion: unlike early Protestant settlers’ manifest destiny in the U.S., full of heathenism and battles against savages within, the Chinese wild was traditionally viewed as a place for curious humans to retreat in solitude for psychological and spiritual well-being. There was no schism between individuals and nature, no need for humans to bend natural forces to their will.

Graphic created by Alex Santafé. Sources: World Bank, USGS, Tsinghua Department of Landscape Architecture,

Mongabay, Pacific Biodiversity Institute, and The Globalist.

Source: The China Project, August 15, 2023. https://thechinaproject.com/…/chinas-other-half…/

Extract from: China’s other half: Wilderness, by Kyle Oberman.